When it comes to historic Milwaukee residences, a few spring to mind, but, none, perhaps, is more iconic than the so-called Lion House, 1241 N. Franklin Pl., even though no one has lived there for four decades.

The house, along with two equally lovely and slightly younger adjacent homes – the Hawley and Bloodgood houses, at 1249 N. Franklin and 1139 E. Knapp St., respectively – have been sold and offered anew as office space.

That gave me an opportunity to peek inside all three and to dig a bit into their history.

At the moment, the Lion House is connected to the Hawley next door via an addition made by the former owners, The Bradley Foundation, not long after they purchased the places in 1995. The new owners, Wisconsin Securities Partners, plan to open a connection between the Hawley and Bloodgood properties, too, so all three will be linked internally.

All three properties have state and national historic designation and are part of the city-designated First Ward Triangle Historic District.

"We are honored to serve as stewards of these historic Milwaukee landmarks, and look forward to working with prospective tenants," said Ross Read, Chairman, Wisconsin Securities Partners LLC, in a statement announcing the purchase.

"Milwaukee is enjoying a great surge of development, and we are looking for those businesses who are moving into the future while honoring the past."

Read showed me around and it was clear he was intrigued by the historical aspects of the homes – plus, his offices are in the 1866 Curry-Pierce Building on the corner of Milwaukee and Wisconsin – so I’d guess his appreciation will translate into preservation.

Though they are all interesting office spaces, with great views, good light and unique layouts, e interiors of the homes have varying degrees of treasures to be saved from a historic standpoint.

But, first, a little background.

Considering how long the Lion House has fired the collective Milwaukee imagination – there were sporadic newspaper articles about it throughout the 20th century – it’s amazing how cloudy its history is.

In fact, folks can’t even seem to decide if the house was built by Edward Diedrichs, Edward Diederich or Edward Diedricks. Nor can they seem to agree on when it was built.

While many more recent sources put the date at 1855, newspaper articles from the first half of the 20th century peg it to 1851. So, I hit the City Directories.

In the 1851 book, Edward Diedricks (sic) lived on Van Buren Street, between Wells and Kilbourn, but by the 1854 book, his home is described as being located on the "corner of Juneau and Prospect," which considering the home that now stands between the Lion House and Juneau Avenue wasn’t built until the 1870s, that seems like a fair and accurate description of the Lion House.

As Diedrichs bought the lot upon which the home sits on Oct. 11, 1852, he likely began construction soon after. The last piece of land he needed to complete the home was purchased in December 1855, which suggests the house was finished in 1856. So, everyone was at least in the zone.

In 1936, the Sentinel described the homeowner as a "pioneer Milwaukeean" born in Germany, who arrived in Milwaukee in 1849, "after the intellectual revolution which swept western Europe. He had lived for a while in Riga – then part of Russia – and traveled extensively throughout the world. Many of his voyages were made with Rudolph Pfeil. Milwaukee’s high bluff and beautiful bay appealed to both wanderers and they decided to make their home here. Diedrichs brought $80,000 with him to his new home. Charmed with the site on what was then Elizabeth Street, he purchased the lot and drew plans for a house."

For the home – which reportedly cost a whopping $20,000 in 1851 money – Edward hired the city’s top architects, George Mygatt and Leonard Schmidtner, who, apparently gave some of the work to their young draftsman Henry C. Koch, who would later design Milwaukee’s City Hall, Gesu and Calvary Churches on Wisconsin Avenue, The Pfister Hotel, Turner Hall and many other gems.

Here’s how the City of Milwaukee’s historic designation report describes the house:

"The Edward Diederichs (Diedrichs) House is a two-story rectangular block which rests on a high brick foundation stuccoed and scored to resemble stone. The low-hipped roof has a large cupola at the center and is trimmed with palmette antifixae. The exterior is clad in cream brick with stone trim. The main facade is articulated by pilasters at the corners and between the bays."

And there are two lions standing guard on either side of the stoop.

William O’Brien, who wrote his Marquette University thesis on Koch, says that the young architect designed the lions, which were executed by Alonzo Seaman or one of the artists in his employ.

"At that time the A.D. Seaman Co. had a factory on Milwaukee Street near the river and was doing excellent work in the woodworking line," noted that Sentinel article. "Diedrichs gave them a sketch of the lions. A skilled workman carved the animals."

That skilled workman may have been Richard H. White. In an 1899 interview, Koch recalled White carved them from an old ship's mast.

In an article a year later, the same paper waxed, "Before the wooden eyes of these two crouching beasts has passed almost the whole history of Milwaukee. Many of the great men of earlier era walked between them, up the wide entrance stairs and into the calm interior of the ancient house."

At the same time, Edward was busy at work altering the bluff a little further south on Prospect Avenue, where O’Donnell Park now stands.

"Diedrichs also spent thousands terracing the bluffs near the entrance of what is now North Prospect Avenue," wrote the Sentinel in 1936. "He made of it a charming summer garden where the residents of that day were wont to repair for picnics, drinking lemonade and beer and eating ice cream, then a novelty."

At his Lighthouse Pleasure Garden, guests could enter without an admission fee and enjoy refreshments at a pavilion and wander down to the lakefront via gravel paths that led to a beach.

An advertisement at the time read, "These gardens are now open for the reception of visitors. The splendid prospect of the bay and lake with their wooded shores as seen from the garden terrace cannot be equaled, and will repay the trouble of a visit."

But maybe he should’ve had a ticket booth, because tough times arrived in the form of the financial Panic of 1857 and Edward’s accounts took a hit. And then more disaster struck.

In 1859, the house was severely damaged inside by fire inside, though the exterior was apparently not badly damaged and the lions emerged unscathed.

"His wife was heartbroken at the damage and told her husband that she would not live in another house: that her beautiful home must be rebuilt," noted that 1936 Sentinel piece. "Diedrichs dared not tell his wife to what state their fortunes had sank. He ordered the mansion repaired immediately. This act took all of his remaining money. Finally he was compelled to leave Milwaukee with his family."

At Edward’s departure, in 1863, his friend Pfeil appears to have moved into the Lion House. Diedrichs is said to have died in a New York poorhouse.

"Pfeil was not at first the financial equal of Diedrichs," wrote the Sentinel. "He opened a tailor shop at Chestnut and Third Streets and at the time of the latter’s financial collapse had prospered sufficiently to be able to occupy the house."

In the pantheon of quirky Milwaukeeans of the past, Pfeil – who lived in the home for but a few years before moving to a house on the east side of Prospect Avenue – must surely have a seat.

The Sentinel’s 1937 article, offers this interesting – if lengthy – anecdote: "Tragedy came to him also. Pfeil’s wife was wasting away from tuberculosis. Knowing that death was not far off, she extracted from her husband a promise that he would cremate her body on the beach of Lake Michigan, at a spot below their house where both of them had loved to watch the lake. Before her marriage Mrs. Pfeil had lived in India, and there were some in the city who believed she was a Brahmin. Others reported she was a Russian countess.

"When she died, Pfeil gathered together several cords of wood on the beach and prepared to carry out her last request. The neighbors were scandalized when they discovered what he was about to do. They thronged about his house and swarmed down to the beach. Sheriff Samuel S. Conover was called, and the outburst of public indignation was such that poor Pfeil was forced to give up his resolve.

"The Sentinel of Friday morning, Oct. 19, 1855, contained the following brief announcement of the incident. ‘The city authorities halted a Russian named Pfeil, who with the aid of several men was constructing on the beach at the foot of the bluff a pyre of 20 cords of wood whereon to cremate the body of his wife, who was a Russian countess and a Brahmin. In her will she requested that her body be cremated, because if this were not done, according to her belief, she would have to die again. Pfeil protested interference, claiming that he was merely carrying out the will of his deceased wife, and there was no law against doing so. But he yielded to the authorities and consented to the burial of the body in the old cemetery on the Menomonee.’

"The rest of Pfeil’s story is unknown. He remains a strange, foreign character in the history of Milwaukee, remembered only for his close association with Diedrichs and his wife’s dying wish. There is even some doubt about his first name. Some historians say it was Rudolph; others say it was Gustav; still others claim it was Gundar. It was generally believed that he returned to Russia after his wife’s death."

Pfeil’s time in the Lion House must’ve been extremely brief because by 1864, Henry Mann arrived.

Something of a renaissance man, the Bohemian-born Mann was a president of the German-English Academy, as well as the director of a number of state railroads and the president of Wilkins Manufacturing – which chairs and other goods fabricated from wood – and Kinnickinnic Realty Company.

In an interesting aside, Mann – born in 1827 and in the U.S. by 1846 – sold land to the City of Milwaukee in 1892 that later became Humboldt Park.

In 1895, banker John T. Johnston – born in Scotland in 1836 – and his family, who had lived in a stunning Grand Avenue mansion, moved in and determined they needed more space and so they tapped architect Howland Russel to add the second floor, made the porch bigger, added a bay on the south side of the house.

Russel also raised the existing cupola to add the second floor.

The architect surely spent a lot of time on the block in 1895 because the same year, he designed the Hawley/Bloodgood Houses (pictured above) in an alluring French chateau style with Gothic spires and other eye-catching elements.

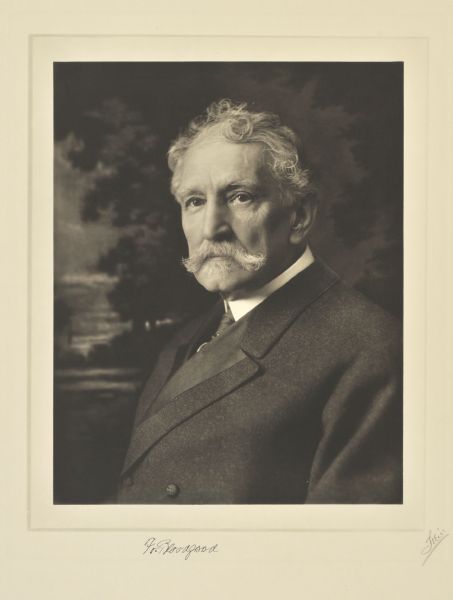

Those side-by-side homes were built by lawyer Francis Bloodgood (pictured at right with his daughter Hilda in an image courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society) and his wife’s aunt Helen Hawley on a plot of land that Mann had purchased three years after he bought the adjacent Lion House and had used as a yard, according to Russell Zimmermann.

Bloodgood and Hawley each bought half of Mann’s lot on the same day.

The Lion House had already become notable and in 1897, George Koch hired architect Edward V. Koch (who were, apparently, not related) to build him a lion house, too, at 3209 W. Highland Blvd., which you can read about here.

Meanwhile Johnston – a nephew of Alexander Mitchell – and his family remained in the Lion House until 1943 (though Johnston himself had died in 1904).

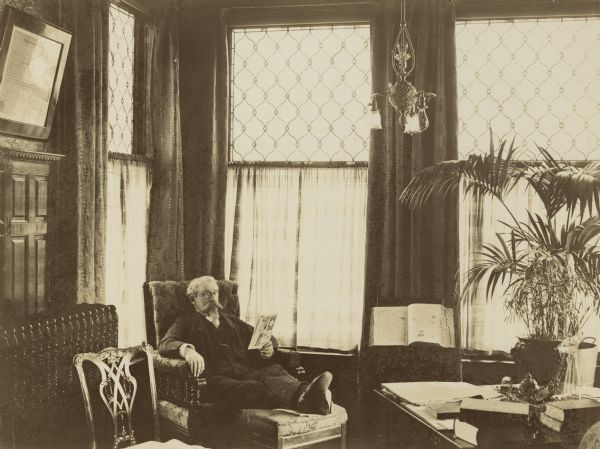

This image of Johnston in the Lion House library and the interiors below,

were all taken in 1900. (PHOTOS: Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

By 1936, his widow, then 81, was already planning to move and held an auction to sell off her reportedly extremely extensive collection of antiques. The sale was notable enough to earn mentions in the newspapers.

"The house with the lions ... so long occupied by the Johnston family, is soon to be abandoned by its chatelaine, Mrs. John Johnston, 81," wrote the Sentinel. "It is said that Mrs. Johnston has long thought the house too large for her needs. She and her son, John T. Johnson, former Milwaukee industrialist, are the only occupants. It is reported they plan to spend their winters in the Southwest."

The sale drew huge crowds of interested buyers and, most assuredly, nosy folks like me and you.

As an interesting aside, the Johnstons’ daughter Hilda was said to have married an English nobleman and, wrote the Journal in 1959, "is remembered by many Milwaukee residents as Lady Butterfield."

According to published sources, Eliot Fitch – an executive at the Marine Bank, the same bank where Johnston had been employed – bought the house in June 1943 for $10,500 and the following year he and his wife Ruth Bartlett Fitch removed the lions which had by then badly deteriorated after living through more than 90 Milwaukee winters.

After Mrs. Fitch died in 1981, the home was sold to Shoreline, a local real estate company, which converted it to offices. At the time of the purchase, newspapers reported that Shoreline planned no remodeling and only a little redecorating to complete the conversion.

Three years later, Shoreline sold to James A. and James D. Hummert, who brought back the lions.

The Hummerts tapped Racine's Al Felch to recreate the original white pine lions out of giant blocks of Honduran mahogany. They also had 29 coats of paint stripped off the cream city brick exterior as part of a $190,000 renovation.

In June 1995, The Bradley Foundation bought the home and added the connector at the back as well as a cream city brick addition that matched the historic details of the home.

The foundation added the oriel window between the Hawley and Bloodgood houses, replacing one removed in 1960.

Now, the foundation is moving on, too, and the Lion House will enter a new phase.

Inside the Lion House, there are still some great moldings, wainscoting, hardwood floors, decorative plaster laurel motifs and the impressive grand staircase added by Russel in 1895.

And, yes, you can climb up into the cupola, which is full of HVAC equipment these days, but the windows are too high to afford a view of any kind without a ladder.

Through the tasteful glassy and modern connector and into the Hawley House, there is a bit less to see. In here, much of the space has been more heavily office-ified, though there is still leaded glass, hardwood floors and wide, attractive fireplaces. There’s also a walk-in safe in the basement for the Hawley family jewels.

A banister (above) and fireplace (below) in the Hawley house.

The real gem of the interiors is to be found in the corner house, the one built by Bloodgood (pictured at right, courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society), with its intimate entrance on Knapp Street.

In here the first floor is a wonder of regal, dark millwork, including a large, stunning entry hall with paneled walls and a lovely staircase tucked off to the side, partially hidden by a hardwood screen with a line of repeated Gothic openings that afford tantalizing peeks below a wide arched space.

Other rooms on this floor have stately exposed beam ceilings and one of them has a broad fireplace in front of which I can easily picture myself with a book in one hand, a snifter of bourbon in the other, a gently crackling fire in the hearth, my dog snoring lightly at my feet.

If anyone’s offering, lions aside, this is the one I want.

Here are some images from inside the Bloodgood house, including a pair of then and now views:

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.